Pelé passed this week, at age 82, and though it probably was no news bulletin that he enjoyed fame beyond belief in his time, it was still humbling to read some of the reactions to the column I wrote about him. Mostly, I hear from folks in the boroughs, in Jersey, on Long Island, in Connecticut, in Westchester and Rockland.

Sometimes we hear from New York’s satellite sister provinces in Florida and L.A. and Vegas. But with Pelé, the addresses were as varied — .uk, .au, .fr; on and on — as the praise for him was universal.

Which does get the imagination whirling.

The concept of building Mount Rushmores in pop culture is not a new one, and the subject has carried many from happy hour to last call over the years. Usually we have modest parameters — the Mount Rushmore of the Yankees. The Mount Rushmore of the NBA. The Mount Rushmore of guitarists. The Mount Rushmore of sit-coms.

Because he and Muhammad Ali were far and away the most famous athletes on the planet in the 1960s, and 1970s, and that was a time long before cable TV and satellite TV and 24/7 news cycles and social media and the kind of instant access we have now. A soccer player scores a goal in Croatia, you can see it in Copiague two minutes later (if you didn’t already see it live).

Pelé, Michael Jordan, Muhammad Ali and Tiger Woods are Sports Mount Rushmore because of their global impact on their respective sports.

Pelé, Michael Jordan, Muhammad Ali and Tiger Woods are Sports Mount Rushmore because of their global impact on their respective sports. N.Y.

Wasn’t that way for Pelé.

Wasn’t that way for Ali.

And yet it didn’t matter where you lived — North Dakota or Nepal, Kansas City or Kazakhstan, Boston or Beijing — you knew who Pelé was. You knew who Ali was. And no matter where either of them traveled, even long after their retirements, they were mobbed by admirers and fans.

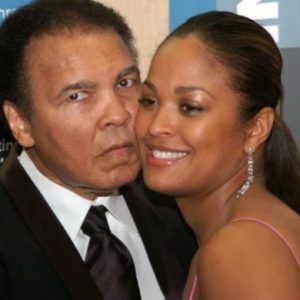

Pelé, left, and Muhammad Ali

Pelé, left, and Muhammad Ali had unmatched influences. Bongarts/Getty Images

So Pelé and Ali are the first two faces on the Mount Rushmore of Sports, Earth Division.

The other two?

This is where it gets tricky. Soccer and boxing are sports with worldwide appeal, which is something that, say, baseball doesn’t have. So as iconic as Babe Ruth was — and remains — in the United States, it’s difficult to imagine that he has the same appeal elsewhere. The same standard applies to American football. Thanks to modern media a lot of people outside the U.S. may know who Tom Brady is, but few have ever actually seen him do what he’s famous for.

Golf is worldwide. And though Jack Nicklaus’ record of 18 majors has seemingly survived Tiger Woods’ early speed, and though Nicklaus is certainly well known and beloved in places well beyond the boundaries of his native country, he never approached the global fame that Tiger did. There isn’t a country on the planet that isn’t familiar with Woods now — when he was winning a couple of majors a year it was even more of a fury.

So I will put Tiger’s face up there, too.

The fourth? Hockey is a global sport, and Wayne Gretzky certainly had a career worthy of consideration since he’s the best to ever do it (and yes, I know Bobby Orr fans feel differently). Tennis has just as much global appeal as golf does, and Roger Federer’s dominance, along with his gentlemanly bearing, have made him iconic just about everywhere.

But I have Michael Jordan as the fourth. Basketball may have started out as a strictly American game, but a quick glance at NBA rosters in 2023 reminds you that it isn’t ours alone anymore, not by a long shot. And though it is a fair argument to ask if Jordan or LeBron James deserves the title of GOAT, the fact is that Jordan’s fame supersedes LeBron’s: Which of the two has a silhouette of himself as one of the most recognizable logos in international marketing, after all?

Pelé. Ali. Woods. Jordan.

Let’s find a few pickaxes and get started, shall we?