All these years later, it is the setting that surprises most of all. Back in 1939, the Atlanta Municipal Auditorium had hosted one of the most glamorous events in the city’s history, a ball to celebrate the release of “Gone With the Wind,” the seminal Civil War-era film set mostly within its city limits.

But on Oct. 26, 1970, a different kind of happening was scheduled.

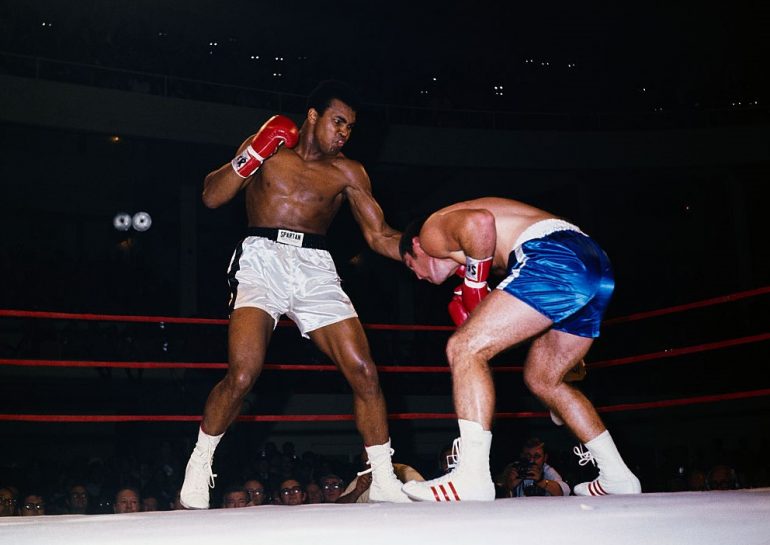

There were 5,100 tickets sold for the night’s main event: a 15-round boxing match between Muhammad Ali and Jerry Quarry. This wasn’t merely a sporting event, however. The last time Ali had entered a ring was March 22, 1967, when he knocked out Zora Folley in seven rounds at Madison Square Garden.

Much of the world — even the sporting press — continued to identify him as “Cassius Clay” before that fight against Folley. It was his eighth title defense as heavyweight champion, and everyone inside the Garden that night — even Ali — knew it might be his last. For months, Ali had declared that he would refuse induction into the Army, citing his religious beliefs.

“This may be the last chance to see Muhammad Ali in living color,” the 24-year-old Ali declared in the third person days before the fight. “So if you have always been wanting to see me, you better come to the Garden.”

And indeed, on April 28, 1967 in Houston, Ali was three times summoned to take the soldier’s oath and agree to become a private. All three times, he refused. He was stripped of his title. He was banned from the sport. Across the next three and half years he earned a meager living giving lectures on the college circuit and fighting a jail sentence, a dispute that would ultimately be resolved, in his favor, by the U.S. Supreme Court.

By the spring of 1970, Ali was older, he was thicker, he had lost what seemed certain to be his prime boxing years. The city of Atlanta was the first to grant him a license. And so it was that Ali-Quarry went on the calendar, scheduled for the Municipal Auditorium, which nine years later was sold to Georgia State University and today serves as its alumni center (now known as Dahlberg Hall).

Everywhere else, of course, this was the dominant sporting storyline. Ali was still a pariah in many circles, condemned as a draft dodger. Even before that he’d been a polarizing figure thanks to his chatty confidence and his conversion to Islam. Still, in an America in which boxing was king, his return to the ring was all-consuming.

There might have been a limited number of seats to witness the bout live, but in New York, there were 17,811 folks who damn near filled the Garden to capacity, paying $7.50, $10 and $15 to watch a four-sided screen showing the closed-circuit broadcast. The Garden cleared a cool $201,000 profit that night. In a world before cable TV and pay-per-view, the closed circuit drew 14,000 to the L.A. Forum, 12,000 to Chicago Stadium, 10,000 in Miami.

In Echo Lake, Pa., in training for an upcoming bout, the reigning champion, Joe Frazier, decided to go to bed at 9 o’clock, skipping the fight, as his manager explained. “because everyone knew Clay would dominate the fight.”

Ali did dominate, beating Quarry in three rounds, looking like he’d never been away. There was much sound and fury surrounding him, still, for his beliefs and his actions. But in the ring, Ali looked remarkably sharp.

“I knew from the first jab,” his trainer, Angelo Dundee said, “that I got the same fighter again.”

Everyone else knew from Ali’s first statement afterward that every other aspect of his makeup was back, too.

“I expect Frazier to be even easier,” he said.

That came in March 1971, and there was no shortage of hype for what remains one of the five most ballyhooed fights in the sport’s history, and one of its fiercest. Ali mailed-in one more bout before then, in December, a lackluster win against Oscar Bonavena. Frazier was there on the other side. And what happened from there … well, it’s history of the finest kind.

The path to that history began 50 years ago this week, in the most unlikely place of all. History happens that way sometimes.