Even as he lay dying, Muhammad Ali continued to amaze those around him.

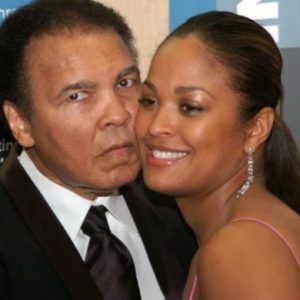

“All of his organs failed but his heart wouldn’t stop beating,” his daughter Hana wrote on social media. “For 30 minutes … his heart just [kept] beating. No one had ever seen anything like it.”

The world paid tribute Saturday to the boxing legend, remembering the man in all his glory and contradiction — as a warrior pacifist, a heavyweight with a lightweight’s grace, a butterfly who, with words and fists, decisively stung.

“Muhammad Ali shook up the world. And the world is better for it. We are all better for it,” said President Obama in a statement on the death of Ali, who died Friday night at the age of 74.

“How fortunate we all are that The Greatest chose to grace our time,” the president added.

The legendary athlete, a native of Kentucky, became the most famous man in the world, known as much for his feats in the ring and way with words as for his conversion to Islam and defiance of the Vietnam War draft.

“I don’t have to be what you want me to be,” he said in 1964, after beating Sonny Liston for the first of his three heavyweight titles. “I’m free to be who I want.”

Later, as Parkinson’s disease robbed him of his speech and steadiness, he became known for his humanitarian work, including a 1990 meeting with Saddam Hussein after which 15 American hostages were freed.

“Ali will never die,” said famed boxing promoter Don King. “Like Martin Luther King his spirit will live on, and he stood for the world.”

He could not win his final 30-years-long bout with the degenerative disease. Ali was admitted to a Phoenix hospital last week and died at 9:10 p.m. Arizona time Friday, succumbing to septic shock. His entire immediate family was at his bedside as his children reassured him that it was OK to “go,” Hana wrote.

“‘We will be okay. We love you. Thank you,’” they told him, Hana wrote on social media.

“All of us were around him hugging and kissing him and holding his hands, chanting the Islamic prayer.”

A public funeral procession is planned for Friday in his hometown, Louisville, followed by an interfaith service during which Ali will be eulogized by former President Bill Clinton, sportscaster Bryant Gumbel and comedian Billy Crystal, who called Ali “the greatest man I have ever known.”

Flags in Louisville flew at half staff Saturday, but the whole world — including presidents and kings — mourned.

“I gave Ali the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2005 and wondered aloud how he stayed so pretty throughout so many fights,” said former President George W. Bush. “It probably had to do with his beautiful soul.”

Clinton remembered a man “who, through triumph and trials, became even greater than his legend.”

King Abdullah II of Jordan called the athlete “a great unifying champion whose punches transcended borders and nations.”

In Great Britain, 28,000 people signed an on-line petition to award Ali an honorary knighthood.

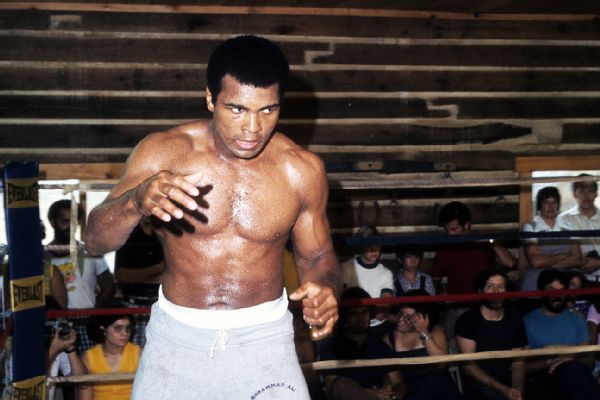

The 6-foot-3, 210-pound pugilist amassed 37 knockouts in a soaring career that included many of the most memorable bouts in history, in such far-flung places as Africa and the Philippines. He finished with a 56-5 record.

Ferdie Pacheco, Ali’s longtime personal physician and corner man, said hitching his wagon to the boxer’s rising star when he was still an amateur known as Cassius Clay was like being “touched by Fate.”

“From Miami Beach to the last Ali/Frazier fight I felt like I had a comet by the tail,” Pacheco told The Post. “It is hard to put into words how amazing it was to be in the company of probably the most famous person in the world.”

His beginnings were humble. And as a 12-year-old weighing 89 pounds.

He reported the theft of his bike to a local cop, Joe Martin, and vowed to find the thief and “whup” him.

Learning how to box might help, Martin offered.

By the age of 18, he’d won an Olympic gold medal — but the achievement didn’t shield him from racism back home, where he was derisively called “the Olympic n—-r” and refused service in a restaurant.

He claimed the heavyweight championship belt in 1964, his agility and quick, dancer-like movements in the ring mesmerizing fans.

By 22, he’d announced what would become his signature: “I am the greatest.”

Ali loved the hot lights of stardom, and was as sharp with his mouth as he was with his fists.

“I’m so fast that last night I turned off the light switch in my hotel room and was in bed before the room was dark,” he once said.

He converted to Islam in 1964. Rejecting Cassius Clay as a “slave name,” he became Muhammad Ali.

When fighter Ernie Terrell inadvertently called Ali “Clay” during a 1967 match, Ali didn’t take it lightly.

“What’s my name?” he demanded in each of 15 rounds as he pummeled Terrell.

The same year he became a political lightning rod when he refused to be drafted into the US Army.

“I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong,” he said. “No Viet Cong ever called me n—-r.”

Convicted of draft evasion, he was banned from boxing and lost three years of his prime. He was sentenced to five years in prison but never served it, remaining free on appeal. The US Supreme Court eventually overturned the conviction, and Ali returned to the ring.

Ali helped change the world with his politics, former NBA superstar Kareem Abdul-Jabbar said.

“At a time when blacks who spoke up about injustice were labeled uppity and often arrested under one pretext or another, Muhammad willingly sacrificed the best years of his career to stand tall and fight for what he believed was right,” he said.

His fights with Joe Frazier and George Foreman were historic, living up to their hyped monikers — “The Fight of the Century,” “The Thrilla’ in Manila” and “The Rumble in the Jungle.”

Doctors believe the price Ali paid for the brutality of boxing was Parkinson’s.

“Just like the rest of us — sometimes you don’t like what the doctor prescribes,” Pacheco said. “I told Ali he must quit because of the damage the doctors were seeing to his brain.”

By the time Ali came out of retirement to fight Larry Holmes, his former sparring partner, in 1980, the years and the disease had taken their toll.

After 10 bruising rounds, Holmes won by a technical knock out when Ali’s trainer, Angelo Dundee, refused to let the legend finish his second-to-last fight.

“I didn’t want to get to him and hurt him and whatever,” Holmes told The Post. “I said, ‘Why are you taking all these goddamn punches, what the f–k’s wrong with you? He cussed me out.”

“I never heard Ali swear until he got in the ring with me,” he said.

After the fight, he went to Ali.

“‘Man, I still love you man,’” he said.

Ali answered, “If you love me, why’d you whup me like that?”